The meaning of the double empathy problem

Traduction française (merci beaucoup, Autisme et Société!)

Well, it’s been a while…

I must confess that I haven’t written a single blog post in a few years – and haven’t posted any in a couple of years. I got busy and distracted, and I guess the idea of writing blog posts turned gradually into a chore instead of what it was supposed to be – a nice way for me to share thoughts1 without going through the rigmarole of peer review, or trying to distill complex ideas into a particular format or length for publication.

However, I’ll try to write the occasional post moving forwards when inspiration strikes.

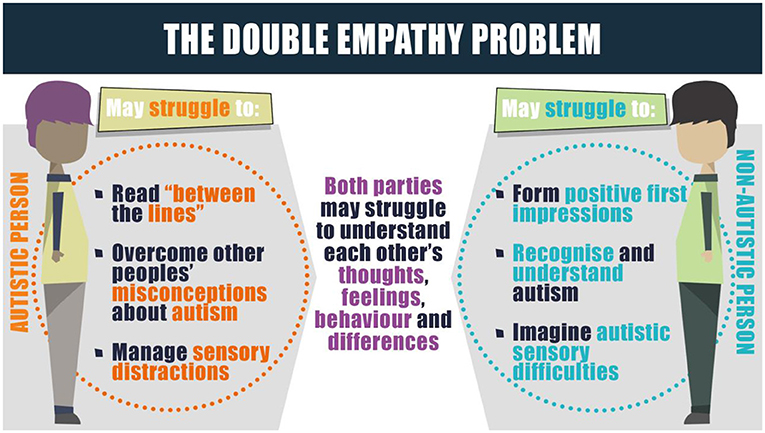

Today, I’m writing about the meaning of the double empathy problem (DEP). What is it, exactly?

When Damian Milton first coined the DEP term, he called it “a disjuncture in reciprocity between two differently disposed social actors,” such as autistic and non-autistic people – a breakdown in communication and understanding. This, building on ideas and observations that were circulating in the autistic advocacy movement,2 challenged the old assumption that autistic people simply had deficits of empathy and social communication skills, which alone caused their social difficulties. Instead, it suggested that many non-autistic people’s failure to understand and communicate with autistic people was part of the problem.

Since then, the double empathy problem has been widely invoked in writing and research – too widely, according to a new paper by Lucy A. Livingston and colleagues. Livingston et al. aggressively criticize the way people use the idea of the DEP, basically saying it is poorly conceptualized and that it is continually being extended into new areas without reason.

But Livingston et al. make an important assumption – in their first few paragraphs, they make it clear that they are talking about social cognitive theories3 and about the mechanisms underlying social interaction. As such, the authors later suggest that the DEP should be “formalized as a theory as per the usual standards in the psychological and cognitive sciences” – standards for theories that are trying to understand processes and mechanisms. Livingston et al. want the double empathy problem to be clearly defined with reference to existing social cognitive concepts, so that we can understand and measure the processes and mechanisms involved.

In short, Livingston et al. treat the double empathy problem as a bad social cognitive theory: a theory that does a poor job of identifying processes and mechanisms. But to me, that’s not what the double empathy problem is about.

I don’t speak for Damian Milton, but to me, the double empathy problem isn’t and shouldn’t be a social cognitive theory. To my mind, the core purpose of the double empathy problem isn’t to understand why non-autistic people sometimes struggle to understand and communicate with autistic people, but simply to recognize that they do. It identifies and describes a phenomenon, or even a set of very similar phenomena; it can be agnostic towards the processes and mechanisms involved.

This makes it useful for advocacy, policy, and applied, action-oriented research – if we know that something non-autistic people are doing is contributing to the difficulties faced by autistic people, we can change the conversation from one about deficits and charity to one about equity and discrimination. A tool that allows us to do this is a powerful tool for social change.

From this point of view, it seems perfectly acceptable for the double empathy problem to be invoked in a wide variety of situations that might involve different causal mechanisms and social cognitive processes. We might invoke the DEP to describe breakdowns in reciprocity, communication, affective empathy, cognitive empathy, and more. In fact, I think it’s practical and desirable to have this sort of wide scope, because it can often be difficult in the complex real world to identify precisely on what level(s) a breakdown is occurring. We may just know that a breakdown is happening somewhere.

From an applied, action-oriented point of view, it might be interesting to know why the breakdown in communication and understanding occurs, but this needn’t be essential. The factors causing a breakdown may not be the same as the factors we could most easily change to resolve the issue, so identifying causes isn’t always necessary to do applied work to fix an issue.

The claims of the double empathy problem

Another question raised by Livingston et al. is what is necessary for one to invoke the DEP idea in any given context. While I will admit to sometimes experiencing a bit of irritation when reading their article,4 I am forced to agree with Livingston et al. that past research has been a little confused about what the core claims of the DEP are/should be. Livingston et al. suggest there are two claims to the theory:

“Claim 1: Neurotypical people struggle to interact with or understand autistic people, just as autistic people have trouble interacting with or understanding neurotypical people.”

“Claim 2: individuals within the same neurotype (i.e., autistic–autistic, neurotypical–neurotypical) are better at interacting with or understanding one another, compared to mixed neurotype dyads (i.e., autistic–neurotypical).”

Claim 2: Unnecessary?

I don’t think claim 2 should be necessary for invocation of the DEP – merely sufficient. That is, if you show that claim 2 is true in a scenario, I think that’s enough for one to invoke the DEP, but claim 2 doesn’t always have to be true for the DEP to apply.

I appeal to the DEP in various contexts, but never with the idea that “neurotypes” such as autism exist as more than heterogeneous, diverse, socially-constructed categories – a view that others, including Damian Milton, share. Autistic people often do connect well with one another, but the diversity of autism is so vast that any two autistic people won’t always “connect,” and that’s fine.

When we view the DEP as a concept that can be useful in an applied sense, I think it becomes clear that the essential contribution of the DEP falls under claim 1 – it emphasizes that neurotypical people struggle to interact with or understand autistic people,5 whereas we might traditionally assume that autistic people are solely responsible for relational breakdowns with neurotypicals.6 To advocate for social changes and to pursue applied research, we don’t actually need to show that autistic people are always better at interacting with one another – just that neurotypicals experience difficulty when interacting with us. This allows us to challenge simplistic models locating deficit in the autistic person alone, and it allows us to emphasize issues of equity and discrimination.

Claim 1: True or False?

And I have to take issue with Livingston et al. on the question of the veracity of claim 1 – they say it’s unclear if claim 1 is true because, in their view, there is not sufficient evidence of autistic people being bad at understanding neurotypicals – or at least, worse at understanding neurotypicals than understanding other autistics. I have two responses to this.7

First, claim 1 doesn’t say, “Autistic people have more trouble interacting with and/or understanding neurotypical people than with other autistic people,” though arguably this is implied. But I would rewrite claim 1 as something like this:

“Insofar as the DEP applies to autism, neurotypical people generally struggle to interact with or understand autistic people (to a greater degree than they struggle with other neurotypical people), just as autistic people generally have trouble interacting with or understanding neurotypical people (often, but not necessarily, to a greater extent than they have difficulty with other autistic people).”

I do think it is true in many contexts that autistic people have more difficulty relating to neurotypicals than to other autistics, but even in contexts where it is untrue – where there is no autistic-autistic advantage – the DEP may still be useful in an applied sense.

If we imagine a scenario where autistic people might be having trouble understanding and interacting with all people (e.g., due to the rapid pace of the interaction, due to distracting noise, due to difficulties taking the perspectives of others regardless of neurotype), we could still invoke the DEP if we can demonstrate that the neurotypical people are having trouble understanding and interacting with the autistic people – that the autistic people alone are not responsible for the interactional difficulties they are experiencing. By invoking the DEP in such a situation, we could justify measures to promote better interaction and understanding by focusing not only on any shortcomings of the autistic people, but also on those of neurotypical people. That, to me, is the core purpose of the DEP.

Second, let’s get back to claim 2. In Livingston et al.’s framework, evidence of autistic people relating well to autistic people is most relevant to claim 2, but I would argue it can also be taken as evidence for the key part of claim 1. If autistic people are better at interacting with and understanding autistic people than neurotypicals are, it seems to follow that neurotypical people must be experiencing some difficulty interacting with and understanding autistic people. And there does seem to be clear evidence of this being true in some contexts. While Livingston and colleagues do direct attention to issues in currently published studies and room to strengthen this evidence base, we already have solid evidence.8 For example, Livingston et al. point out that autistic-autistic pairs and nonautistic-nonautistic pairs in this study didn’t have exactly the same level of rapport – they just each had better average rapport that autistic-nonautistic pairs – but it’s not at all clear to me how Livingston et al.’s observation here in any way contradicts claim 2, or what I view as the core of claim 1.

But what are the mechanisms?

However, I agree with Livingston et al. that a better-developed understanding of the science underlying the reality of the double empathy problem would be useful. There’s fascinating research that helps to identify and distinguish some of the processes and mechanisms that might be involved, but the investigation of such processes and mechanisms hasn’t really been pursued systematically. While it might not be strictly necessary to know the cause of a problem to address it, I’m sure that a better understanding of the factors involved would help us address the DEP more effectively.

I’ve written up a little list of some of the things I suspect could be involved, at least insofar as the DEP relates to autism, and that might be directions for such research:

Different Minds, Different Perspectives?

Most obviously, non-autistic people might have trouble understanding a mind-brain that thinks differently from theirs – giving rise to difficulty with cognitive perspective-taking and mentalizing. Autistic people’s experiences and thoughts might be sufficiently outside a non-autistic frame of reference that most people would really struggle to understand autistic people’s points of view.

Similar Minds, Similar Perspectives?

Relatedly, we can flip this around, and say that if autistic people have similar minds, they might be more likely to find taking one another’s perspectives relatively easy. This might give rise to circumstances under which claim 2 could be true – autistic people might understand other autistics, and neurotypicals might understand other neurotypicals, but neurotypicals and autistics might struggle to understand each other.9

Similar Minds, Other Similarities?

Moreover, if people share similar minds, they may share other factors that could promote better interaction. We’ve long known that friendships and other social relationships are more likely to develop when people are similar (show homophily), and there are complex reasons for this, but the straightforward fact that people often like to hang out with others who are similar to them is an important part of it. For example, there are different ways of using conversation (e.g., is conversation for sharing information, complaining, gossip, etc.?), and people who think alike might share preferences in this regard. These sorts of similarities could result in more enjoyable and successful exchanges.

Common Ground from Common Experience?

However, I hardly need say that autism is incredibly diverse and that not all autistic people do think alike. Autistic people are incredibly diverse in so many dimensions10: cognitive ability, motor skill, sensory reactivity, and more.11 This diversity clearly exceeds that found in the neurotypical population.

This could limit the extent to which autistic people share similar perspectives, relational styles, preferences, and so on. Nevertheless, autistic people might be treated in similar ways by neurotypicals, because of our common divergence from the norm. We might have common experiences of being misunderstood or mistreated – perhaps for similar reasons and in similar ways. This might give autistic people a common frame of reference that many neurotypicals would lack, and might give rise to some of the circumstances under which claim 2 could still be true despite the immense diversity of autism.

Flexible Social Norms?

Moreover, broader norms around interactions are vital to consider here. Perhaps due to our common experiences of being outside the norm,12 autistic spaces usually have a different set of social norms to neurotypical-dominated spaces. As Idriss writes, autistic communities are often highly flexible, and Heasman and Gillespie show how interactions among autistic people can be characterized by a low demand for coordination that makes it relatively easy for interactions to continue despite disruptions. In contrast, conventional neurotypical interactions – with their greater, more inflexible demand for coordination – could be derailed by people “going off script.” This could also give rise to circumstances where claim 2 is true – where autistic-autistic dyads interact well – even if the autistic people are unlike one another.

I suspect this might be especially common in more complex situations, where flexibility is possible. Tightly-constrained laboratory studies might therefore show “weaker” forms of the DEP, or fail to observe it entirely, compared to more complex situations. In that vein, Wadge and colleagues (2019) conducted an interesting study which showed autistic people really struggling to communicate with other autistic people in a very specific situation – they had to communicate solely by moving shapes in patterns they felt would convey information. This didn’t leave autistic people any Plan B – flexibility and openness weren’t helpful when there was no other way to communicate. Findings in a similar study from Edey and colleagues weren’t quite as bad – in that study, the autistic people at least weren’t worse at communicating with fellow autistics than with neurotypicals – but the autistic people still struggled even when communicating with fellow autistics.

In contrast, in the complex real world, if we fail to relate in one way, we can adopt flexible social norms and try again another way. Thus, studies like those of Crompton and colleagues (e.g., this and this) – taking place in more complex situations – seem to generally find evidence for a stronger form of the DEP.

Power and Perspective-Taking?

Another important consideration is the fact that autistic people are a marginalized group, and frequently find themselves under the authority of neurotypical people. The reverse situation is considerably less common.

Prior research generally suggests that people who have less power over others – all else being equal – tend to be better at perspective-taking. This makes sense: if others have more power than you, you need to be paying attention to them, understanding their point of view, and predicting their actions – after all, their decisions could affect you! On the other hand, if their actions and decisions don’t matter to you, why bother?

Thus, it’s not surprising that neurotypical people wouldn’t necessarily be very adept at understanding the perspectives of members of a group of people who invariably occupy subordinate, marginalized positions with limited power.

Identity?

I won’t belabour this, since Livingston et al. mentioned it, but whether people know that somebody is autistic could also be important.

If people know somebody is autistic, that could lead to prejudice, bias, dismissal, etc. Conversely, it might lead people to become aware that they are applying neurotypical norms and frames of reference that aren’t applicable, and to adjust accordingly. Which of these scenarios ends up being the case could be quite complex and depend upon many factors!

Social Flow?

As noted in a recent article, autistic people’s increased susceptibility to flow states might enhance the experience of interpersonally connecting with other autistic people. That is, not only might some of these other factors support connectedness between autistic people and their fellow autistics, but autistic people’s intense and persistent focus might further enhance and prolong such episodes of connection.

Conversely, neurotypical people might find it harder to enter the states of social flow sought and valued by autistic people, reducing neurotypicals’ success at interacting with autistic people.

The scope of the double empathy problem

Thus, we can get a sense that there are likely many processes involved in the DEP. This relates to another question – Livingston et al. also ask whether the DEP applies exclusively to autism or whether it could also apply to other groups. I think it’s easy to see how many of the processes discussed above could operate in contexts outside autism.

However, Livingston et al. also ask whether we can use the term DEP to refer to any level of disjuncture or breakdown along a continuum, or whether some definite threshold must be reached. This is an interesting question. From an action-oriented, applied perspective, I suppose we could invoke the DEP concept in any situation where we feel it is useful in advancing some objective. This could be done quite creatively.13 But invoking the DEP to highlight the difficulties faced by marginalized neurominorities who experience discrimination and exclusion seems quite distinct from using the DEP to resolve about a minor disagreement between two friends, for example! Thus, I personally feel that the DEP concept makes the most sense in situations where we are dealing with marginalized groups and individuals who have been blamed for relational breakdowns that at least partly reflected failings of members of dominant groups.14

Implications of the mechanisms and processes

A further key insight we can obtain from the list of processes and mechanisms that might be among those involved in the DEP is that most of them do not necessarily and inevitably lead to relational breakdown. For example, if many neurotypical people are too inflexible to have interactions that don’t follow conventional patterns, they can learn to be more flexible. Power doesn’t always reduce perspective-taking: if the powerful feel responsible for others, they can show more understanding of others’ perspectives. Even something like autistic experiences being outside a neurotypical frame of reference isn’t insoluble: neurotypical people can learn from autistic people and come to better understand autistic perspectives.

Thus, it seems that the DEP is indeed modifiable – and from an applied perspective, this is excellent. Our understanding of relevant mechanisms and processes can help us more effectively make changes to promote understanding and successful interaction with autistic people.

As I suggested earlier, the factors “responsible” for a breakdown in communication or understanding may not always be the ones we want to change to resolve the breakdown. For example, let’s suppose that a breakdown is (at least partly) caused by a neurotypical person’s low propensity towards entering flow states. Individual proneness to enter flow states might be a relatively inflexible and difficult-to-change trait,15 and anyway our neurodiversity-affirming respect for others’ personalities and dispositions would caution us against even attempting to change it, so trying to encourage neurotypical people to be more flow-prone doesn’t seem like a good solution. However, other solutions – like encouraging the neurotypical person to adopt more flexible social norms – might still help.

Indeed, even identifying the factors causing a breakdown will often be quite difficult in real-world scenarios where many processes might be involved. Thus, when I say that understanding processes and mechanisms can help us resolve issues, I mean that these simply show us factors we might be able to leverage to make changes.

And making these changes is important. The DEP concept has helped to expose an ever-increasing number of areas in which neurotypical people’s (mis)interpretations, (mis)behaviours, and (mis)judgements contribute to the social marginalization and exclusion of autistic people. I have no doubt that the phenomenon of the DEP is real, and I am therefore confident that conducting more rigorous research related to the DEP will provide additional empirical support to the concept and enhance our ability to use it to pursue applied goals.16

- This is a polite way of saying “to rant or vent about topics on my mind”.

- Like in the celebrated satirical definition of “neurotypical syndrome” on Autistics.org, or Xenia Grant’s 1993 quote that, “Very often it’s the so-called ‘normal’ people who lack empathy because many of them don’t want to listen to any point of view besides their own.” In fact, Ava Gurba just pointed me as I was writing to a Twitter conversation about an article Jim Sinclair wrote as far back as 1988 that articulates core aspects of the DEP idea, stating, “When I am interacting with someone, that person’s perspective is as foreign to me as mine is to the other person. But while I am aware of this difference and can make deliberate efforts to figure out how someone else is experiencing a situation, I generally find that other people do not notice the difference in perspectives and simply assume that they understand my experience. When people make assumptions about my perspective without taking the trouble to find out such things as how I receive and process information or what my motives and priorities are, those assumptions are almost certain to be wrong.”

- Theories about cognition/thinking related to social interaction.

- I think mostly because of the tone – there’s such a long legacy in our field of the “experts” asserting their superior knowledge, and ignoring that of autistic people, that the article really “rubbed me the wrong way,” as it were. The article simply seemed patronizing, I suppose. Indeed, at risk of the authors saying I’m committing a fallacy by extending the double empathy problem idea without an adequate rationale, I might even say that the lack of consideration of how the lecturing tone could offend people may have reflected some level of a double empathy problem-type issue… (That last sentence was mostly a joke, but not entirely!)

- Or that some other dominant group struggles to interact with or understand a marginalized one.

- Or that other marginalized people are solely responsible for relational breakdowns with members of dominant groups.

- Well, three – my third response is just that I find it slightly hilarious that the DEP is being attacked for insufficient evidence to support a claim of a specific autistic deficit!

- Plus my anecdotal lived experience, which leaves me with little doubt about the veracity of the claim in many important contexts. When members of a marginalized group say XYZ is true about themselves, their claim may or may not be correct, but I do think that, generally speaking, the burden of proof should be on the dominant group to disprove the marginalized group’s claim.

- Though in practice, because there are so many more neurotypicals than autistic people, autistic people may have had more opportunity to practice understanding neurotypical perspectives, which could complicate the picture.

- Not that we can measure the dimensions perfectly.

- And different subdimensions within these dimensions as well, like fine vs. gross motor, or reactivity to loud stimuli vs. subtle irritating ones!

- Leading to a greater sympathy for those who are different, and perhaps a greater unmet desire for social connection, etc. It could even reflect the vast diversity of autistic people – we might have more tolerance for unexpected behaviour by our interlocutors because it is so difficult to find others who are exactly like us!

- For example, I like to complain that neurotypicals are inflexible, which is very different from the traditional neurotypical complaint that autistic people are inflexible. I think it’s an important point and making it has applied value. I have sometimes called this a “double flexibility problem,” essentially drawing on the DEP idea by analogy to a new domain. It’s creative and makes sense, if I do say so myself. At some point, I’m sure we will want to do further research on this and develop a convoluted theoretical model of the circumstances under which autistic people or neurotypical people may be more or less “at fault,” and the different mechanisms involved in their respective brands of inflexibility, but for now, I deem that off topic – it isn’t necessary for us to be convinced that neurotypical people are sometimes inflexible, and that this double flexibility problem idea has applied value in getting neurotypical people to confront this reality and change their ways.

- Broadly conceived – I’m not just talking about groups within liberal identity politics, such as neurodivergent people or ethnic groups, but also groups like socioeconomic classes.

- To be clear, yes, there are many contextual factors that affect whether somebody is likely to enter a flow state at a given time. But some people just appear to be overall more prone to entering flow states – with autistic people generally appearing more flow-prone than neurotypical people – and changing that overall level of flow proneness is the part I’m saying is problematic.

- Of course, I’m not opposed to the idea of having social cognitive science. The generally progressive pursuit of knowledge within a post-positivist, more-or-less Kuhnian framework that (though slightly cynical at times) is ultimately inspired by and oriented towards pursuing the ideals of reason, science, and the Enlightenment, is one of the things I most passionately care about in the whole world! And if we can no longer justify a theory based on evidence and logic, then that theory may not be of much applied value – if we’re trying to make the world better, we have to be guided by evidence and reason to know how to do so effectively. But if we are dealing with an applied concept developed to advance the interests of marginalized communities, our primary motivation should be to uncover information that could be useful in that applied sense. If our question is just about the basic science of social-cognitive processes, then it may still be a worthwhile question, but a different type of question.

7 thoughts on “The meaning of the double empathy problem”

It seems to me that what Livingston et al. were trying to raise wasn’t that autistic people don’t have interaction problems, but that they don’t have problems understanding neurotypical people. And I tend to agree with this statement; in fact, we (autistic people) have no problem understanding neurotypical people; we just find their way of functioning vague, hypocritical, and irrational, which makes it a way of functioning that we find stupid, and rightly so, I think! And so, there wouldn’t be a double problem of empathy, but a one-way problem between neurotypical people and neuroatypical people. In truth, I don’t believe a neurotypical person truly understands another neurotypical person, since they don’t say anything meaningful to each other for fear of creating conflict.

Great piece, Patrick. Really appreciate your analysis. 🙂

Really appreciate!! I think it would be great for you to write a formal reply to Livingston et al. paper through a journal article so that your ideas will be more accessible to researchers

Thanks Kit and Cheryl for the kind words! In fact it does seem like I may be joining a more formal academic response as well, even though that wasn’t my original intention…

In fact it does seem like I may be joining a more formal academic response as well, even though that wasn’t my original intention…

I’d love it if you created a link to the English language version on your website. You only have a link to the French language version, and parsing the output of the translation engine is headache-inducing.

Sorry, to clarify the translation I linked is the French translation of this English language post. The academic response is still being worked on.

I very much enjoyed reading your response to Livingston et al Patrick – tho’ I am yet to read this paper myself. I surely will, shortly, with more time on my plate! There is a whole research program within your response 🙂 that I hope you or others will pursue.