Networking and Planning Careers

Have you heard the term “hidden curriculum” before? It refers to everything that is not explicitly taught in a place of learning.

One important part of the hidden curriculum in a university – the setting where people are getting an education in preparation for undertaking a professional career – is how to actually go about getting a career. Universities teach people academic information – facts, theories, and so forth. Information about how the world works. We don’t really discuss how that can be translated into useful careers.

Even when I participated in my undergraduate university’s work experience program, there wasn’t much useful information provided. Just a lot of insipid, professional-sounding boilerplate about developing “professional competencies” and suchlike. It was all so vague and abstract as to be, for all intents and purposes, largely meaningless.

Instead, a lot of the useful information about jobs and careers comes through word of mouth. What is it like on a day-to-day basis to work in such-and-such a field, or to go through a graduate program in this discipline? What are the job tasks and what are the social demands? What sort of qualifications and experience would people expect from an applicant in a certain field? Should one be going out and getting volunteer or work experience during one’s university studies?

For example, I’m a graduate student studying experimental psychology. Just having an undergraduate degree in psychology isn’t enough for psychology graduate programs to consider you as an applicant: you need to have psychology research experience. Most people start by volunteering as undergraduate research assistants, and then they will often complete a research project for an Honours thesis. After graduating with a bachelor’s degree, many students will go on to get a lab manager job for a year or two before they apply to graduate school programs. There’s really not much point trying to apply to graduate programs without some research experience – it’s just expected that you will have it. Unfortunately, this is not something that undergraduate psychology classes discuss!

I was simply fortunate enough that I got my undergraduate research experience in psychology when I was early in my undergraduate studies – I started in my second year. Honestly, I don’t think I had much of a sense of what I was doing at the time, but from there, I was able to make social connections with professors and graduate students and learn about the steps towards getting into psychology graduate school.

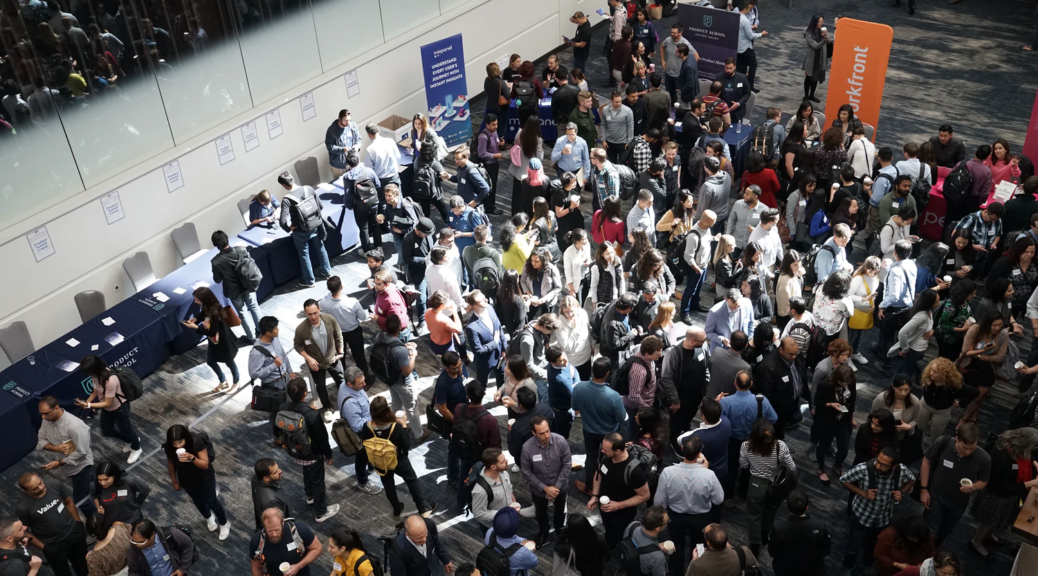

This is how people learn about getting into fields of work and study. They don’t learn it in classes – they learn it through networking.

This system is problematic on a number of levels. For one thing, I’m sure it discriminates against first-generation students whose families don’t have a sense of how the university environment works or what is necessary to do well. (The families might think that getting good grades is the important thing, for example. In reality, good grades are only one of various things that might be needed for graduate school, and I’m not sure grades are very important at all outside of academia.)

The existing system also discriminates against autistic people, since social networking is not our thing. We need to equalize the playing field by providing students with an explicit overview of some common career paths and what might be required for each: something to get people started in pursuing whatever paths might interest them. And by this I don’t mean a bunch of meaningless business jargon – I mean genuinely useful information that actually describes the expectations of different fields.